Continuing from Unstealthing, Incrementally.

I have many ideas for applications, but most of them seem to rely on similar kinds of infrastructure, in particular a distributed, secure application-level messaging system. Unfortunately, this doesn’t really exist yet, at least not in any form that meets my needs.

What am I talking about here? More colloquially, it’s a mechanism for letting applications all over the network send messages to each other, without requiring a central server, and without allowing messages to be eavesdropped upon or faked.

Let’s take it one buzzword at a time…

Distributed.

I don’t know about you, but I’m getting fed up with centralization. It happens because it’s the path of least resistance: buy a domain name, rent a server, buy more servers and stick a load-balancer up front as your user base grows. It’s solving problems by throwing hardware at them. The end result can certainly work fine, but too often it’s fragile: both technically (site goes down, ten million users get pissed off) and politically (just one domain for China to censor, one company for France to file lawsuits against.)

In social software especially, there’s an additional type of cultural fragility, since the owners, implementors and users of a big social site have different goals and massively different levels of power. Many examples have shown that this creates sites that scale up into the equivalent of planned communities, shopping malls, theme parks, marred periodically by the protests of an angry minority of users against what they see as privacy intrusions or censorship.

Unfortunately it’s hard to use the Web architecture in a distributed way. This would involve lots of small groups (or individuals) running their own Web-based services that interoperated seamlessly. There are certainly technologies that help with this interoperability, such as OpenID and web services (whether REST or SOAP), but the bottom line is that setting up any kind of Web based system is a task that’s way beyond nearly all end-users, just as it was in 1994. It just never got any easier! You still have to know about FTP uploads and file permissions and CGI-BIN directories and Apache logs and MySQL configuration, even to set up something trivial like a damn blog.

So the options for Web-based social software end up being (a) Install it yourself on your vanity domain, if you’re a total geek and don’t mind doing your own tech support; or (b) Patronize some hosted service that will take care of it for you. What happens then, as popularity of this medium increases, is that the hosted services get bigger and bigger, money pours into them, they go into arms races of feature creep and marketing, they get even bigger, and voila! It’s MySpace and FaceBook all over again.

So that leads me to distributed non-Web-based systems. Which are completely untenable because the only way you can run custom oddball software on a real server is to rent your own private server (or virtual one), which costs orders of magnitude more than the regular web hosts that just let you run CGI scripts. Or if you want to run server software on your computer at home, you find that your consumer broadband connection comes with throttled upload bandwidth, no fixed IP address, and terms of service that forbid you from running servers.

Do you see where I’m going? Peer to peer. It’s the ultimate decentralization. If you resolve the scaling problems at the protocol level, then none of the network nodes need unusual amounts of horsepower or bandwidth, and the total supply of both naturally increases along with the user base. Installation of software on desktop computers is a cut-and-dried problem: it’s as easy as downloading and double-clicking an app. And the content is completely in the hands of its creators and users: no Disneylands, no thought police, no ad beacons.

Secure.

“Secure” means a lot of things. In a messaging system, no legit user wants messages to be spoofed, tampered with, censored, read by the wrong people, or sent by the wrong people.

In the Good Old Days, no one worried about this because the net consisted of a few thousand geeks with Ph.Ds who pretty much trusted each other. (And that’s why email is so pathetically vulnerable to all the attacks I just listed.)

In the present day, developers focus on making their big monolithic servers secure from intruders, and the end users mostly trust that the developers are (a) doing a good job of that, and (b) not doing anything unethical themselves with the customers’ data. It mostly works out, I guess, although there are daily reports of embarrassing security holes, crazy new types of cross-site-scripting attacks, “creative” uses of sensitive customer data for marketing purposes, and backup tapes of millions of customer credit card numbers being accidentally left behind on the bus.

The more you think about that, the less crazy it seems to trust a peer-to-peer system where there are no authority figures handing out accounts or enforcing access privileges. Because in such a system you have to actually make everything secure by design instead of just trusting people. Want to create an identity that no one can steal? Generate your own key-pair (and keep your private key safe!) Want to keep the wrong people from reading something? Encrypt it. Want to prove you wrote something and keep anyone from altering it? Digitally sign it.

It’s not like there aren’t any known solutions to this stuff. It’s just that applying them can be tricky, and so far it’s generally been easier to just lock your big server up in a data center instead.

Application-Level Messaging.

What I mean by this is that the messages sent between users’ computers are not necessarily directly human-readable. Unlike emails or instant messages, they might not be delivered right to the screen, but rather to an application that presents them differently. For example, a message might represent a move in a chess game, a revision of a shared document, or a notification of new content stored elsewhere. Sending these as emails or IMs is awkward and relies on having the user intervene by opening file enclosures or URLs.

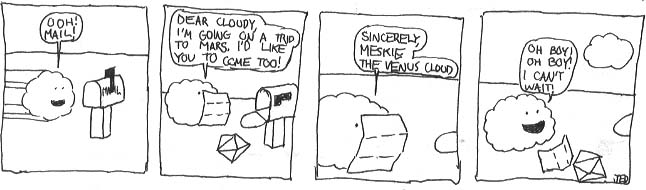

*Next: How Cloudy Does These Things